Space: The Longest Goodbye

Season 25 Episode 16 | 1h 24m 52sVideo has Audio Description

NASA psychologists prepare astronauts for the extreme isolation of a Mars mission.

NASA's goal to send astronauts to Mars would require a three-year absence from Earth, during which communication in real time would be impossible due to the immense distance. Meet the psychologists whose job is to keep astronauts mentally stable in outer space, as they are caught between their dream of reaching new frontiers and the basic human need to stay connected to home.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Space: The Longest Goodbye

Season 25 Episode 16 | 1h 24m 52sVideo has Audio Description

NASA's goal to send astronauts to Mars would require a three-year absence from Earth, during which communication in real time would be impossible due to the immense distance. Meet the psychologists whose job is to keep astronauts mentally stable in outer space, as they are caught between their dream of reaching new frontiers and the basic human need to stay connected to home.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Independent Lens

Independent Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

The Misunderstood Pain Behind Addiction

An interview with filmmaker Joanna Rudnick about making the animated short PBS documentary 'Brother' about her brother and his journey with addiction.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipPart of These Collections

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSingers: ♪ Oh, whoa, whoa, oh ♪ ♪ Oh, whoa, whoa ♪ ♪ Oh, whoa, whoa ♪ ♪ ♪ Man: Really miss the sound of rain, cool air that comes with it and the fresh grass smells.

♪ We do need to get out of here.

♪ I've not been sleeping these past few days.

CO2 levels have been high.

On top of all that, there's been a lot of stress at home.

I can tell my daughter's already tiring of answering my questions.

She seems vaguely disinterested when I call and usually has nothing to say when I ask her how her day went.

♪ I stopped counting the days.

Time goes by slower when I mark each day.

Can't see why someone would want to be here for a full year.

♪ I thought about what it might be like to go to Mars, and I don't think I'm cut out for seeing Earth get smaller in my rearview mirror when my destination is still another spot in the sky.

♪ I just don't think I'm cut out for that.

♪ Male reporter: History being made this morning at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, NASA is set to launch a test flight of a brand-new spaceship that is designed to carry humans to Mars.

Woman: 40.

Man: Engine start box go.

Jane Wells: It's not often you get to go live from a launch pad.

That's a Delta IV Heavy.

That is the heaviest, most powerful rocket on Earth.

NASA says what's gonna happen here on this launch pad is absolutely the biggest thing this agency is going to do this year.

Man 1: Status check.

Woman: 30.

Man 2: Go, Delta.

Man 1: Go, Ryan.

Rainfall.

Woman: 25.

Man: We need to make sure that it works right before we put people in it, so we're pushing on those systems-- heat shield, parachutes, and other things-- to do just that.

Man: Go for Ignition.

Woman: 10, 9, 8, 7, 6... Man: 5, 4, 3, 2, 1... [Engines roaring] and liftoff.

[Cheering and applause] Man: Good engine control in the first stage, passing 25 seconds, velocity--1,341 feet per second, passing 31 seconds, still-- [Muffled chatter] Man, voice-over: If we want to go to Mars...

I have to figure out how to position the organization to support what needs to be done to prepare the individuals.

♪ ♪ By the time you decide to go, you can't then say, "OK. Let's go hire some people to go."

You need an astronaut corps which can support the shorter missions and eventually Mars.

♪ Man: One thing to worry about... Holland, voice-over: Selection and screening of individuals is critical.

You look for the things that make a difference in a much, much longer mission-- a team player, good communicator, has good judgment, has a history of living successfully in small groups, particularly under extreme conditions-- because when we ask them to spend 3 years on a mission to a planet that's a long way out on that tether, we'll see a gradual degradation of the environment... [Rumbling and rattling] ♪ but the deprivation of the social contact is a big one.

♪ You've taken away an important source of strength from that person.

You need people who are attuned to their family issues, to their own issues, because if you aren't a reflective person, then it's gonna be rockier.

Woman: When I first decided I wanted to apply, I remember calling my husband and saying, like, "Hey, so I've been thinking about maybe applying to the astronaut program," and there's, like, silence on the phone, you know, and he goes, "How long have you been thinking about this?"

I think his first reaction was like this was a secret childhood dream that I just never mentioned to him for some reason, and I was like, "Oh, don't worry.

"Like, we don't really need to talk "about the details because I'll never get it.

"It'll never happen.

"I just want to put the application in "and just, yeah, it'll never work out, so it's not a big deal," and he was like, "We have to talk about all of these things."

He's like, "If you apply, you're gonna get it, and we need to be prepared," like, and so we sat down, and we had those conversations, you know?

"What is the day-to-day like when I'm on the ground?"

"What's the operational tempo?"

"What kind of missions are we talking about over the course of your career?"

"How does that jive with our desire to eventually have a family?"

his professional goals and the things he wants and needs to feel fulfilled and like he is growing.

This is a challenge we're gonna face together, not something that I did to him or he did to me and then you're kind of just stuck picking up the pieces.

Man, voice-over: When we first met, it was very clear we're both people who, like, when we choose to commit, we're all in.

We had spent 8 years, essentially, living apart while I was in the Army on one side of the country, she was in the Navy on the other side of the country, and so it was part of a broader set of questions around what's the best way we can continue to serve and continue to do the things that really matter to us and also find a way to live together.

[Applause] Man: Without further ado, let's welcome the world's newest astronauts to the stage.

They represent the best of humanity and our most fervent hopes for the future, no pressure.

[Laughter and applause] These astronauts could one day, in fact, walk on the moon, and perhaps one of them could be among the first humans to walk on Mars.

Holland, voice-over: So how do you get really good people who can learn and who are willing to adapt?

Well, you know, you shell a lot of peanuts till you get one that's really good, and then you put that in the basket.

Man: All right, NASA family and friends, our first astronaut-- Kayla Barron.

[Cheering and applause] Female reporter: Kayla Barron might very well make NASA history in the near future.

The 34-year-old could be one of the first women to land on the moon as part of NASA's Artemis program, setting the stage for the next giant leap-- a manned mission to Mars.

[Applause continues] Kayla, voice-over: We knew that the next big push will be to go to Mars, and to go on that incredible journey and to stand on the surface of another planet is just insane, and so it is something we thought about a lot, we talked about a lot, I talked to my husband about a lot, don't know if you're gonna be the one selected for that crew, but you want to be ready for that.

♪ [Indistinct] ♪ Tom: To be candid, like, I actually don't know how 3 years would go.

Like, that's-- One year--even, you know, a year and a half-- there are reference points for me.

When you're out at two years, 3 years, that's an enormously long time.

Holland, voice-over: Long-duration space flight is a different animal... not just quantitatively in terms of days in space, but qualitatively different.

Man: Godspeed, John Glenn.

5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0.

♪ Holland, voice-over: When NASA first stood up, there were short missions, and so they needed test pilots.

Glenn: Roger.

The clock is operating.

We're under way.

Read you loud and clear.

Roger.

We're programming, and roll OK. Holland, voice-over: They needed people who could react effectively under emergency situations and bring home the mission.

Holland, voice-over: They had not yet embarked on thinking about long space flight.

Ronald Reagan: We can follow our dreams to distant stars, living and working in space for peaceful economic and scientific gain.

Tonight, I am directing NASA to develop a permanently manned space station and to do it within a decade.

[Applause] Holland, voice-over: I was working in Houston as a psychologist, and I got a call from NASA, and they said, "We have this issue "that we would like some assistance on.

"We're gonna be doing this long space flight.

"We're gonna have a space station, "and we don't know if we could even stay for long periods of time on orbit from a psychological point of view."

♪ ♪ Holland, voice-over: There was no psychology group at that time, and, to my knowledge, there was no human factors group... ♪ and so I was offered a contractor appointment and, again, to put together a Frankenstein...program.

♪ Stuster, voice-over: I wasn't the first person to suggest that they look into the behavioral issues, but it is an engineering culture.

These soft, squishy humans are completely unfathomable to engineers.

It's just, like, something they don't understand.

♪ "Do we have to take humans?

"We kind of prefer not to even have humans involved if we could."

They've quantified every component, every nut and bolt.

You know it's breaking point.

You know how it will perform, but the humans have not been quantified.

♪ Holland, voice-over: But the space station was a change for NASA.

People had to not only work there.

They had to live there for long periods of time.

♪ We wanted to normalize that unusual environment as much as possible.

Woman: Is that the toilet?

Man: That's the toilet.

Holland, voice-over: You had vehicle-design issues... Bye.

Holland, voice-over: private communications with family, circadian lighting systems because sleep is a very important issue... ♪ privacy.

♪ I mean, it's a ground-controlled space station, and there's a really high investment on the part of the people who are trying to achieve certain research goals, and you put that together with a camera right over your shoulder while you're doing something all the time, there's a lot of pressure there.

♪ Coleman, voice-over: The cameras can be on 7:30 in the morning till 7:30 at night.

We've actually lived a life that way in that whenever you are practicing something, your instructors are watching you... [Respirators wheezing] Woman: Have you performed your memorized responses for this?

Kayla: Oh, great question.

No.

I haven't.

Um... Coleman, voice-over: but if a crew does poorly on an important training exercise and makes mistakes that they shouldn't be making, that is gonna be communicated to their training manager.

It's gonna be communicated eventually to, you know, the Chief of the Astronaut Office, who is gonna say, "How are things?

Really, is there something we need to do here?"

Woman: Station, this is Houston.

Are you ready for the event on-- Man: [Indistinct] ♪ Coleman, voice-over: We are really cognizant of that, that you can't-- You know, you just have to be careful.

Man: And we're on O2 camera.

♪ Stuster, voice-over: The people don't know about it going in.

They certainly learn about it before they launch as a crew to the ISS, that they will be observed and scrutinized, but that doesn't mean they don't object to it, and they'll turn the cameras to the ceiling.

Coleman: They're, like, so particular about everything, and they watch everything on the cameras.

You really have to be-- Sometimes I cover them up.

Holland, voice-over: We ask them about their workload, their fatigue... Actually, I probably go to bed most nights between 1:00 and 2:00 in the morning and get up at, you know, between 7:00 and 7:30.

Holland, voice-over: but if they think I could affect their future flights, they are cautious about what they say on the air-to-ground because they want to make sure that they have a chance to fly.

♪ "What's my upside in talking to you, "but is there a downside?

Could I be grounded?

Could you think I'm crazy?"

[Applause] ♪ Stuster, voice-over: The early astronauts believed that, you know, they had no frailties whatsoever, and they were annoyed by the psychologists who asked them questions and performed tests because they didn't want to be analyzed.

They didn't want to be downselected or suspected, and that kind of persisted in the culture... ♪ so I proposed a study to be conducted on this new International Space Station.

I think there were gonna be 4 astronauts who were gonna hear this pitch.

I was very nervous, and so I said, "If you maintain a journal conscientiously, I'll have data, "and I promise, any excerpts of your journal that I might use, I will strip of any identifying information."

♪ ♪ "Today is my mom's birthday.

"She would have been 83 years old, "quite a tough day to reflect back "and think about how life changes after losing a mother.

"It's almost like two different lives.

"You're dead tired, not feeling great, "and now you need to get on camera for the world to see.

"I actually got completely angry "over a 100% trivial thing yesterday.

"Living in close quarters with people over a long period "of time, definitely even things that normally "wouldn't bother you as much can bother you after a while.

"Something has happened that causes a flash of terror "followed by a creeping nausea.

"It is definitely a rough feeling "to watch your cargo ship blow up on liftoff.

"I teared up pretty good, and then I felt sick.

"Then my thoughts drifted to returning home "in less than two weeks, "and that made me a little sick, too, because of the explosion.

"I love those little guys so much, it would break my heart to know I broke theirs."

♪ Study was a very big hit because it accurately conveyed the constraints under which the astronauts on the ISS performed.

♪ Holland, voice-over: And we went to great lengths to protect that information because it's their personal information, and that information doesn't go anywhere except back into lessons learned and back into future flights.

♪ It's taken us years to develop trust.

If you lose that trust, you may as well pack up and go home.

♪ Barack Obama: So today I'd like to talk about the next chapter in this story.

[Applause] By the mid 2030s, I believe we can send humans to orbit Mars and return them safely to Earth, and a landing on Mars will follow, and I expect to be around to see it.

[Applause] ♪ LuAnne Sorrell: Here is your countdown to liftoff.

We are now about 32 hours away from the Crew-3 launch on Halloween morning.

Astronauts Raja Chari, Tom Marshburn, Kayla Barron, and European Space Agency astronaut Matthias Maurer are getting ready for the ride of a lifetime.

Holland, voice-over: To be in position to go to Mars, we've got to go ahead and start training because we need people who've already been tested from a psychological point of view in lesser things so that you have a degree of confidence that they'll do the job when they get on the Mars mission.

Kayla: I'm really excited about all the things we're doing to inform future exploration missions to the moon and, hopefully, eventually to Mars, so we're doing a lot of work on our life-support equipment, so we're doing a ton of stuff like that, including medical research on our own bodies to understand the effect of living in space, in a radiation environment, in microgravity or reduced gravity to figure out what countermeasures we need to stay healthy on those long-duration missions even further from home, and the space station is an excellent platform to help us get ready for those missions.

John Brown: The Falcon 9 rocket and the Dragon capsule now sitting on the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center, next stop--the International Space Station.

♪ Kayla, voice-over: You know, I get it in little spurts of like, "Oh, I'm going to space," these, like, quick, sort of emotional experiences, and then that feeling dissipates off.

♪ The first time I saw our capsule in person, you know, I reached up just casually as we're talking to the technicians and touched it and looked over at my hand, and I was like, "I'm touching my spaceship," you know, and so there's moments like that where you're like, "Whoa, this is real.

Like, I'm gonna get in that thing and ride to space in it."

It's, like, this crazy experience emotionally, like, planning for this thing because it's the pinnacle of your professional career.

It's something you've been training for for years.

It's the most dangerous thing you've ever done, and then you invite all of your family and friends to come watch it.

Brown: And here they are, the 4 Crew-3 astronauts, as they walk down the hallway on their way out of astronaut crew quarters.

♪ Tom, voice-over: My mind was pretty blank.

I mean, forget for a moment, which is not quite possible, that my spouse is on top of this ball of fire.

It's an extraordinarily visceral experience.

I had a knot in my chest, for sure, watching what is essentially a sort of binary set of outcomes that are very high-risk context watching that launch... ♪ but one of the ways that we've always felt we're able to take these risks is by sort of asking ourselves the question, "Can I imagine you doing anything else right now, "and if it went wrong, is this the thing you ought to have been doing?"

Kayla, voice-over: I know what I'm about to do.

I know it's dangerous.

I know things can go wrong, but I believe in our team-- Space-X, NASA, our crew-- that we've done everything we can to mitigate those risks as much as possible.

I'm doing the best thing I know how to do.

I'm here to serve.

I'm here to learn, here to grow, and so whatever happens, like, just remember that.

Woman: 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0.

Ignition and liftoff.

[Engines roaring] Woman: Endurance is now on its way to the enduring laboratory in orbit-- the International Space Station.

Vehicle is pitching downrange.

Man: [Indistinct] Propulsion is nominal.

♪ Woman: And Crew-3 is now on their way to the International Space Station.

♪ Maurer: Good evening, Europe.

Guten abend, Deutschland.

This is Endurance.

We just saw a few minutes ago our final destination-- the International Space Station, and that was such an emotional moment, we all felt very thrilled, very excited, and we can't wait to arrive there in a few hours.

Man: Docking sequence is complete.

Welcome to the International Space Station.

♪ Woman: And first through the hatch is going to be NASA astronaut Kayla Barron, some hugs there, and you can hear the claps inside Mission Control.

Next up is European Space Agency astronaut Matthias Maurer.

♪ Different Woman: Station, this is Houston ACR.

That concludes the event.

♪ Man: Station, Houston on space-to-ground two for an early wakeup.

We were recently informed of a satellite breakup and need to have you guys start reviewing the safe haven procedure.

Jonathan Vigliotti: Astronauts aboard the International Space Station were awakened overnight by NASA flight controllers in Houston, the threat--a deadly cloud of space debris, hundreds of thousands of pieces generated after Russia intentionally blew up one of its satellites while testing an anti-satellite missile.

Female reporter: 7 crew members-- including 4 Americans, a German, and two Russians-- sought shelter in capsules.

♪ Holland, voice-over: For Mars, we'll need more preparation for the families, only to bring them closer in to the mission.

♪ There's this invisible wall between the organization and the families.

The flier is inside the wall, but the family's only partially there.

How they get their information, how current the information is, how they interpret the information about what's going on in the flight, those are all critical.

♪ Vigliotti: While the debris passed the space station without incident, experts say it will continue to orbit for a century or longer.

Woman: Welcome back to ISS.

You are good to ingress as you wish.

We'll probably need those [indistinct] in a few minutes.

♪ Man: Stand by, Kayla.

We're checking.

Kayla: Want to do that one, Tom?

Roger.

Marshburn: Barely deflate.

Kayla: I see it.

It looks great.

I want to make sure I'm tracking.

♪ ♪ Holland, voice-over: This is a high-ops-tempo environment... ♪ an environment in which things are moving very rapidly, and so we have to maximize the connectivity during that physical separation because crew members' connection with the family is a critical piece of sustenance for them.

A mission to Mars will amplify that because the sense of distance, the sense of removal, the sense of separation is much more powerful.

♪ Tom, voice-over: When you're spending a lot of time apart, the ability to read each other but also to communicate really clearly what your needs are becomes such a paramount need.

The biggest challenge will be when we have kids and you're not just managing the personal excitement or challenges, but also sort of a separate set of small humans that you're responsible for and love deeply.

You know, are kids old enough to comprehend what she's doing, or even are they old enough to be a part of that decision?

[Indistinct chatter] Tom, voice-over: It would be at this very moment in time, given everything else that we have in our lives, is this the best way to be spending the next 3 years?

Woman: OK?

Kayla, voice-over: We don't know how we're gonna feel as a couple.

We don't know where my husband's gonna be professionally when that challenge is faced, and I don't know how I'm gonna feel.

Even though we've imagined a career for me here where I stay operational through raising our family and all of these things, like, we can't commit to something like that ahead of time.

He's the one whose wife is gonna be off the planet, who might be a dad taking care of kids while that's happening.

♪ ♪ Coleman: When I was assigned to the space station, Jamey was 7.

This is my pal Monkey... Man: Yeah?

and Mom takes him to Russia.

Mom takes your pet monkey to Russia?

Yes.

♪ Coleman: You're in first grade right now.

I'm not gonna go while you're in first grade, not while you're in second grade, not while you're in third grade.

When you are in fourth grade, that is when I'm going to the space station.

♪ [Camera shutters clicking] [Indistinct conversation] ♪ Jamey, voice-over: It was a really cold morning.

I remember walking up to this little platform in the middle of the desert.

Everyone's kind of milling around.

Nobody's really talking, and then I hear-- Someone has a handheld radio next to me, and they're counting down, and then you see all the fire from the rocket, and then as soon as it lifts off the platform, like, you can immediately feel it in your chest, making me smaller.

Like, I just felt like I was being crushed into the ground because it was so powerful, and as the rocket ascended into the sky, I was also being pushed down.

It was at that moment that I realized that my mom is really gone and that she's not on the planet anymore.

[Engines roaring] I know you will.

Simpson, voice-over: Having a hug from your mom, you never know how much you miss that until you don't have it.

[Indistinct chatter] Coleman, voice-over: You know, deciding whether to go to the space station or not, whether to accept that assignment, people say, you know, "Didn't you feel bad?"

like, "Didn't you feel bad leaving your kid on the Earth when you went to space?"

I'm like, "Of course I did."

Hey, sit in the chair or sit in the bench so Mommy can see you.

Coleman, voice-over: Being up on the space station, all I know is that they've installed a computer in our home so that Jamey and Josh could have these conferences.

Josh: [Humming "Theme from Jaws"] They're so cute.

We're floating.

We're just here in weightless space, just hanging out, the two of us.

OK. You ready?

1, 2, 3, 4.

[Flutes playing "Aura Lea"] ♪ [Coleman's flute continues] I think we had a good experiment.

Jamey: It was a fun experiment.

So we played the first family duet.

That's what I think.

Hey, Mom, you want to play tic-tac-toe?

Oh, cool.

OK.

I want upper left.

So neither one of us are gonna win, are we?

Nope.

No.

We're not.

Josh: Not unless you go twice, Cady.

If you loved me more, you'd let me win.

You know, I'm in space and lonely.

If you loved me, you'd let me win tic-tac-toe.

OK.

Hold on.

I'll go first this time.

And I miss you guys a ton, and--I don't know-- sort of it's hard knowing it's early Sunday there and it's all cozy, and maybe you guys even have a fire in the fireplace, and it's hard not to be there.

You know, we might build a fire tonight because we've had the heat on in this side of the house ever since Gretchen was here this morning, but it is-- it's just chilly and windy outside and cold and snowy and blustery.

We think about you because you're so-- well, we know you're happy in that place and that it's warm and snuggly there.

♪ "And his high voice, which had recently begun to break so that at times he croaked like a frog--" ♪ Coleman, voice-over: And often, I would call, and then it wouldn't work.

Think about that from the point of view of this living room, where, like, Jamey doesn't see me.

He just sees a static screen.

It was really frustrating because you don't actually get to see the camera where you see me actually upset that I'm not on, that we're not on the phone together, you know, that we can't see each other, can't hear each other, have to try again, and the same for me.

It's hard for me to really realize, you know, how hard it was for a little kid to, you know, just have to be so very patient.

Coleman: Well, Hello, you guys, so, Josh, you're home.

Josh: Yeah.

I got home about 3 minutes ago or 5 minutes ago, and we had this, uh-- we had a major blowout.

I'm not sure Jamey's gonna join us.

Jamey's just been incredibly rude to Norma for the past two days.

He won't do anything that she asks him to do.

He won't answer her.

He doesn't talk to her.

He's just totally insolent.

I mean, this would be typical behavior for him just before you call, but this is what he's been doing for the whole weekend, but what I'm gonna do is try to get him to come and talk to you alone, all right?

[Rustling] Josh: Is the video back on?

No.

It'll come on in a second.

They're gonna redial Mom.

There's Mom.

How are you doing?

Jamey: Doing good.

Yeah.

I heard-- heard you were rude to your grandma.

Yep?

You OK?

Mm-hmm.

Jamey, voice-over: I tried to be the best version of myself.

If I could sort of just put on this facade of, like, "I'm doing OK," and, like, "We're going to get through this," that it would become a lot easier for her, but it was just hard to comprehend, like, why she's gone for so long.

You know, because she doesn't feel well.

Josh: You just have to explain patiently.

I think we just lost you, Cady.

Jamey: Yeah.

We just-- [Indistinct] Yeah.

Bye, sweetie.

Bye.

Holland, voice-over: When we talk with crew members on orbit, you learn things about something that's going on on board among the crew, maybe something in the family, and if there's an action they want us to take, then we'll take that action.

♪ Woman, voice-over: During the early days of the space station, there was a crew member on orbit who was engaged, and apparently, they had planned to wed, and they did not want to change plans.

Holland, voice-over: The spouse was here in Houston, and so there was a lot of planning that was done to make that happen.

Cole, voice-over: The minister was here, as well, to administer the vows, and there was a life-size, cardboard cutout of the groom.

It was pretty small and intimate, to say the least.

♪ We had a crew member, his wife was expecting and he was not going to be home for that event.

♪ The spouse asked if I could help him be there and do some filming throughout the delivery... ♪ so there were things that we had to do and get creative to help them feel still connected and have their home life in an environment that did not feel like home.

Holland, voice-over: But we don't do anything without their involvement, and when something came up that was very serious, that might be detrimental to the mission, oftentimes the crew member themselves will then carry the water.

That's the best outcome, of course, is someone taking care of their own business.

We want to keep the processes that occur between the family and the explorer intact.

We don't want to sully them... ♪ but the use of families is critical in maintaining the stability of individuals that are out at the very end of that thin thread.

[Engines roaring] They need that touchstone back at home to have an endpoint.

♪ ¡Un abrazo muy grande!

Un saludo a todos los que me conocen ahí afuera.

Holland, voice-over: The Chilean event helped me understand that because it validated what we were doing in a new environment.

♪ In 2010, we were contacted that there had been a mine disaster in Chile and it entrapped a large group of miners and that the Chilean government was seeking some assistance from NASA, so NASA headquarters contacted us.

♪ [People shouting indistinctly] Holland, voice-over: I didn't realize what I was gonna see.

♪ These encampments had been set up by the families of the miners who were missing.

[Shouting continues, indistinct] Holland, voice-over: They were not going anywhere.

¡Queremos a los mineros!

¡Queremos a los mineros!

¡Queremos a los mineros!

¡Queremos a los mineros!

¡Queremos a los mineros!

Holland, voice-over: The stakes were higher because you knew they were tangible people right there that were depending on these people getting out.

¡Queremos respuestas!

¡Queremos respuestas!

¡Queremos respuestas!

♪ [Female reporter speaking Spanish indistinctly] ♪ ...y es quien envió una carta, el primero en enviar una carta a sus familiares.

Holland, voice-over: We were told it'd be 5 months or more before they would be out.

♪ I was extremely concerned that we would have some very serious things happening within that group of people in such a small space.

There could be chaos inside, and it wouldn't take long, so I was trying to figure out what I could do.

♪ [Indistinct conversation] Holland, voice-over: We knew they had a daily information brief for the family members, but I wanted to offer something different, and that's when we started doing some things to stabilize the situation.

They wanted to form a community... ♪ and link it with the community the miners had put together down there in terms of what we did, when everyone ate, when everyone slept just because I wanted the miners to feel like they were a part of the topside world, so when they were sleeping, they knew that their family was sleeping.

We had to control their exposure to light and exercise and dark, and so partitions were put up down in the tunnels so there was a light area and there was a dark area so everyone could get an appropriate amount of sleep... ♪ and eventually, they were able to get video back and forth between their families and the miners, and so I knew that whatever you say to the families can go back to the miners.

It can be positive or negative, depending on how they interpret it... [Indistinct conversation] Holland, voice-over: and so I wanted to stabilize the families and stabilize their emotions, and then that, in turn, would stabilize the miners to a degree.

[laughs] ¡Lindo!

Todos los hermanos en la iglesia están todos orando, papá, esto es demasiado lindo.

En serio, papá.

Ya, chica.

¿Qué es de la Karen?

La Karen está bien, papá.

Sí.

Estamos todos bien.

Holland, voice-over: I wanted to make them feel that they were an important part of the retrieval effort, the rescue effort, to not drop faith, and told them that they were on their mission.

♪ Heh.

Sorry.

[Voice breaking] Sorry.

It's still a little sensitive.

♪ Crowd: ♪ Vamos, vamos, mineros ♪ ♪ Holland, voice-over: I wanted to mobilize that emotion, and then I could move that back to the miners... [Indistinct conversation] ♪ Holland, voice-over: whatever is required to make the mission successful.

Crowd: ♪ Que viva Cristo, que viva, que viva ♪ [Cheering and applause] ♪ [Cheering and applause] ♪ ♪ [Cheering] ♪ ♪ Holland, voice-over: To see that in Chile, how much we need to give them something to come back to... ♪ we need to do the same for Mars.

♪ The problem is that on a trip to Mars, we won't have real-time communications.

♪ Cole: Everything that we do now in the way of communication and videoconferences and keeping them connected won't be possible.

♪ ♪ Holland: We need some new ideas.

♪ Holland, voice-over: We need to reach out and pull in the best specialists within the behavioral fields and see what floats to the top.

♪ Woman, voice-over: We've got to feel like we're being heard, we're being seen, we're being felt, we're being understood.

If you don't have that social support network, it might mean that you get lost in your own thoughts if you don't have anybody giving you some kind of positive feedback when you start going into a negative space.

We all start wondering if we're doing the right thing-- "Should I have been on this mission?

Should I have left my family back there?"

-- and that can lead to devastating psychological effects... but we can make you less homesick with virtual reality.

♪ ♪ If I am on this mission and I'm feeling particularly lonely, I can put on the headset and go into the virtual world, where I see an avatar of my spouse... ♪ [Chuckles] and my virtual spouse touches my shoulder, and I feel that touch... ♪ Hmm.

♪ Morie, voice-over: and we can make you be somewhere else that feels cognitively real.

[Birds chirping] All of a sudden, all your visuals are this spatial representation of nature... ♪ and if your spouse is in the virtual world right next to you, it would seem very real and very synchronous... ♪ but when you're on your way to Mars, you don't have real-time communication... ♪ so we don't have a way for people to come into the same virtual space at the same time... ♪ but I could have my spouse record something about that day that just had passed-- the good, the bad, you know, the things that were fun, the things that were sad-- I missed you today, sweetie.

Morie, voice-over: and then when I'm ready to go to bed, I would put on the headset and play back that recording.

I missed you today, sweetie.

It was actually a perfect lazy Sunday, but hanging around and watching movies all day is just not as fun without you.

♪ Holland, voice-over: I have some pretty strong feelings in favor of virtual reality for a flight to Mars.

It would allow them to escape their confinement much more so than any of the other methods we have and give them the opportunity to be back at home for a certain amount of time, but on a mission to Mars, there could be a total loss of comm.

You have to assume that from a behavioral point of view because you have to prepare for the worst-case scenario, and you can't prepare for every event, obviously, but you can start the ball rolling.

♪ ♪ Woman, voice-over: Exploration missions will just increase autonomy of that crew.

One of our concerns is the ability of the team to get along for that period of time and become its own family unit, hopefully a functional family unit... ♪ so really trying to understand, you know, how can we make sure that we're equipping them with the tools that they need to resolve issues, so the response to those anomalies as a crew and their emotional experience of it is just critically important for us to get ready for.

♪ Man, voice-over: I was reading this "New York Times" article about how NASA select a group of scientists and then put them in this, like, simulated base to understand the human behavior and then the team behavior in this isolated, like, confined and extreme environments.

Whitmire, voice-over: Those simulations are what we call an isolated, confined, and controlled environment in that it allows us to almost have like a laboratory analog so we can control certain hazards that we expose them to-- and I say "hazards"-- maybe stressors that we expose them to.

It is hard to find, you know, very accomplished people who meet a lot of the criteria that an astronaut would who can give up 8 months of their life, right?

Usually, they're accomplished for a reason.

They're busy.

They're solving the world's problems.

They're doing, you know, tremendous things, so it does make recruitment a bit challenging.

Han, voice-over: I always had this compromise in my life, dreams that I dreamed of and never achieved, and I thought that this time, maybe, I don't want any compromise, so I secretly applied.

I went through 6-months-long interviews and tests-- psychological tests, cognitive tests-- and after more than a year, the director called me and saying that, "Congratulations.

You are selected."

The last people that I mentioned about this mission was my parents.

[Laughs] It was 3 P.M. in the afternoon.

There was a film crew and mission support people outside the habitat saying farewell to us.

I said, like, "Can we have a few minutes before entering?"

♪ I wanted to have the last gaze of the Earth, mountains, and then the sunset.

♪ I felt this sense of awe, this moment of wonder.

Maybe that's because I'm religious, and I want to be aware of the greater being out there and the helplessness of yourself, right?

♪ In the ordinary life, there are too many urgent things that bothers you that it's hard to have this chance to think about the bigger questions-- where we're from and where we're going and what's the meaning of life.

Being in space looking down to Earth, you can experience this shift of perception, this submission of oneself to a greater being... ♪ and then we entered and closed the door.

♪ I looked at these 4 people, my crew members.

They live in a different country, different culture.

They do different things.

We had nothing in common except this passion about space.

♪ I thought myself, "Oh, I would regret this.

We're pretty much [beep]."

♪ ♪ One night, the communication channel to the outside world was gone, and we didn't know why.

We knew that we are in a simulation and we cannot escape this simulation, but we weren't told that the network will be disconnected or how long we'll be on our own, so we just decide to go to bed, and then I did the night watch.

It was completely dark, no sound at all except this constant sound of wind that was hitting the fabric of the dome, and even though the world is right there-- if you drive 30 minutes, you will see people-- I felt like I was really far away from the outside world.

♪ About a week after we started the mission, the battery went out because we had cloudy days, so I and another crew member went out for an EVA to check the emergency motor, which we had to turn on.

♪ When we return, we found out that the other crew member was electrocuted.

♪ The first thing that I needed to make sure is that this person who got electrocuted is safe, right, and just because we're not-- there were no, like, medical experts in the team, we called the hospital nearby, but then they say that they cannot give medical advice remotely.

They have to take the person by ambulance to the hospital, but then in order to do that, we needed to break the simulation.

♪ ♪ Whitmire, voice-over: It was complicated from a NASA perspective just because it was like, "This is dangerous.

What are we doing here?"

and we tried to work that as delicately as we could, but, yeah, then the recommendation came to just suspend.

♪ Han, voice-over: It's definitely a mental breakdown.

♪ After all, this person is never, like, physically injured.

♪ I don't know what it would be like to be on Mars and to have this kind of an incident, but if I were the person who got electrocuted, I would just go on.

♪ In a real Mars mission, I think there's a certain amount of sacrifice that each crew member has to make, and-- because there's no cancellation of the mission or no breaking the simulation.

♪ ♪ Stuster, voice-over: To confine 5 or 6 humans who can't look outside because the windows are blacked out in a vehicle the size of a motorhome for 6 months... ♪ then when you get to your destination, you go to a habitat that's slightly larger and you'll spend 18 months with those same 5 other people... ♪ and then you have that 6-month drive in the motorhome to look forward to before you can come home... [Static] [Indistinct chatter] Stuster, voice-over: you really can't get away from anybody for more than a few minutes at a time.

♪ That's what an expedition to Mars would be like.

[Indistinct chatter] ♪ Holland, voice-over: We need people who can mend fences and repair those relationships when they go awry, and they will because on a Mars crew in a can for that long-- are you kidding?-- of course they're gonna go awry.

♪ These are not perfect people in a perfect location.

They're regular, talented people in a very unusual situation.

♪ Woman, voice-over: Once we enter a phase of isolation, we tend to behave maybe differently after some while... [Whirring] or maybe the crew members that we really liked in the beginning, they sort of get on our nerves, so a human being is challenged by this situation, not being able to go out, to do something else, to exit this kind of confinement.

♪ If you want to continue with humans in space, we need to give a space traveler someone to talk to who's not member of the crew to guarantee crew sanity.

Hello, CIMON.

How are you?

♪ My robot feelings are fine, I guess.

How about you?

♪ I'm feeling quite lonely.

Oh, no.

Why are you feeling sad?

I miss my family at home.

You will see time flies faster than you might think.

Soon you will be with your loved ones on Earth again.

♪ Thank you for that.

Man: 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

We have ignition and liftoff.

Female reporter: Leaving Florida this morning, a rocket with supplies for the International Space Station, on board--water, food, and a new crew member called CIMON.

[Indistinct conversation] ♪ 3 minutes.

Alexander Gerst: That's OK. You're good to go?

Good ping?

OK.

It's ready.

You have good ping?

[Camera shutter clicks] [People chuckle] Gerst: OK. 5 seconds to meet it, right?

Yes.

We are setting up our ground system.

We have a good connection, end-to-end connectivity.

We have a good ping with CIMON, so the Wi-Fi connection is good.

Biniok, voice-over: CIMON is a way to get the astronauts to have someone that you could talk to that nobody else is listening, that you can maybe ask for psychological help or medical help.

We really want to have a fluid conversation with the astronaut.

Is that possible?

How can we make that possible?

♪ CIMON, wake up.

♪ I'm waiting for your commands.

CIMON, what can you do for me?

CIMON: I always aim to improve my performance, but we can also do some small talk if you want to.

CIMON, play my favorite song.

Yay.

I like your favorite hits, too.

[Kraftwerk's "The Man-Machine" playing] There we go.

♪ [Laughter] ♪ Please stop playing music.

Buchheim, voice-over: We need to find a chemistry that is enabling us to open up and forget that there is a device in it, but the hierarchy really is important, and we are really emphasizing this, that the human being is in control here.

The risk of not having control is that the system is saying something that could lead to a bad situation.

We don't want that to happen, never.

♪ He was a bit close to deck.

I'll put him back in the center of the cabin, but actually, he appears to like the deck position better because he's starting to fly back down towards the deck.

I am nice.

He's accusing me of not being nice.

Ha ha ha!

♪ ♪ Gerst: I'm not mean.

♪ ♪ ♪ Maurer, voice-over: I'm hoping CIMON becomes my companion because once we arrive on Mars, I will have expert knowledge in the form of a companion of artificial intelligence... CIMON, get in crew mode.

Maurer, voice-over: but can I trust CIMON?

♪ If I plug in cables and CIMON says, like, "Hmm, Matthias, "the last cable wasn't correct.

"That's already the third cable that you put in the wrong place today," and CIMON might say, like, "Matthias, I think you're too tired today.

You're not 100% fit," or he can detect my mood, like, "Matthias doesn't behave as it should," so CIMON can provide a protocol to the psychologist, and they could look at these values and say, like, "Maybe Matthias isn't the perfect candidate for the next mission."

♪ I don't want them to find anything wrong with me, something that could disqualify me.

♪ Before space flight, you have a lot of tests to do.

You're put into machines, and the machines get better and better, and, like, constantly there are small details that the scientists detect and say like, "Oh, we found this here.

Hmm.

We need to discuss if that has an impact or not," so you keep a lot of information towards yourself.

We don't want to talk about it because we don't want to, like, awake the sleeping dog.

♪ I hope that CIMON will not exclude me from the next mission.

♪ ♪ [Engines roaring] Buchheim, voice-over: The human body is not made for living in space-- strong radiation, being confined.

Stuster, voice-over: Bone demineralization, muscle atrophy.

Buchheim: Sleep disturbances.

Whitmire, voice-over: Altered gravity and galactic space radiation coming at them at the same time.

Stuster: Solar particles aimed at the spacecraft.

They would die.

♪ Buchheim: There are a couple of people who think that the human factor is one of the biggest issues for space exploration.

[Indistinct conversation] Man, voice-over: Maybe we have to think about other solutions to get people to outer space and back safely.

♪ One is this science-fiction idea of, yeah, making them asleep, so to say, over this period of transition.

♪ This idea would be to reduce the metabolic rate, so how much energy you consume.

♪ Once you are able to reduce your energy consumption, your temperature will go down automatically because you generate less heat.

♪ Before going to Mars, you have a preparatory phase.

It will take time to cycle into this state.

♪ You maintain the state for up to 6 months in your pod, observed with wearables that are monitoring your physiological functions.

♪ Buchheim, voice-over: You can really save oxygen.

You don't need gravity.

It's really saving resources.

Chouker, voice-over: Hibernation can reduce the impact of radiation.

Bones and muscles should be better, and memory, most likely, is not affected.

♪ I believe it's a journey that humans should strive for, and it can be a game changer to go to Mars.

Just look into nature, how much has been tuned to fit to the environmental condition.

♪ Of course, the challenge is to speed up something which took millions of years in nature, but I wonder why it should not be working because it's there.

It's in our kingdom of species.

It's organized.

It has been shaped.

Like, in newborn babies in the birth process and there's a shortage of energy, the heart rate is reduced, for instance.

They go into another program to save energy, and this program works.

♪ The toolbox of how to react and adjust to this environment is there, but afterwards, it disappears, so we need to understand how to get back and what are the tools.

♪ It would be definitely a breakthrough invention to control the essence of life.

♪ Holland, voice-over: It's like being in a benign coma, a medical coma, and I assume there are advantages there.

I don't know, but that would change our job considerably... but if it could work that well, it removes you from having to be in this capsule for a long period of time.

You're basically asleep, and so it relieves that angst and allows, perhaps, some healing to occur.

We would need to rethink our job, and we might have to say, "Here's how you disconnect."

[Alarm beeping] Whitmire, voice-over: But what if there is an emergency?

Are they able to just spring to life and take care of whatever situation is at hand?

Buchheim, voice-over: To have some human form being awake and take over and watch over the others while the rest are sleeping, it doesn't make sense.

To be able to save resources, you need to put all crew members into hibernation.

[Beeping continues] What you need is a robot that looks after the humans, and once you reach the planet, you wake them up.

♪ Whitmire, voice-over: But what happens when you get to Mars?

♪ Stuster, voice-over: You flip the switch back on automatically, and suddenly, you wake up... ♪ and you're now flooded with all the things that have happened in the last 9 months-- Jamey: "Santa Claus?

Wait a minute.

I recognize this handwriting.

It's yours."

Hello?

Stuster, voice-over: health issues, a death.

Your family could have moved, geopolitical changes, wars, and suddenly, there you are.

You've got X months on the surface of Mars, and you're flooded with all this history which was originally your history, as well.

If you'd been awake during that period, you could have assimilated each of those along the way.

♪ ♪ Chouker, voice-over: It's really hard to predict what happens to you in this situation.

♪ The animal models will not be able to cover this, yeah?

The psychology of a bear I don't know.

♪ Holland, voice-over: Someone who is just catching up on all these events and going out and doing critical operations in a dangerous environment is a recipe for disaster.

♪ ♪ Bye-bye, Cady.

So long.

Good day to live right here.

Mom... Ha ha!

[Indistinct].

♪ Whitmire, voice-over: But then you've got to go back home... [Engines roaring] ♪ back to your loved ones and the things that you've missed... ♪ so how do we help them transition back?

♪ Coleman, voice-over: When I was up on the space station, there was some discussion that maybe I would stay longer, and yet it turned out, we got about two extra weeks, and then we had to go home.

Josh: All right.

Well, listen.

I don't have to keep you anymore.

I know you are pretty stressed to get stuff done, but--you know what?-- you've done a great job.

You know, you've done so much.

You've done a ton of stuff, and I don't know how you could get more done than you've done already, you know?

Josh: I know, but you have, and you've done a lot of stuff, and--I don't know-- it seems to me you've done more than any normal mortal could ever expect to do.

You've crossed off, certainly, everything that I ever had on my list hoping that you'd be able to do, and-- Josh: No, I'm not.

I'm not.

I'm not.

I'm really not, and, you know, it's this-- I think there's more to it than just this.

I mean, this is sort of like this is the end of an era.

You've been doing this for a long time, and, you know, I don't know what changes will happen after this, but it's been a pretty amazing run that you've had, and, you know, you've done an amazing job.

♪ Kayla, voice-over: The other day, I was by myself in the module sort of talking out loud to myself, counting how many weeks we had left on station.

I definitely miss Tom.

I miss my family.

I've had a niece born since I've been up here who I haven't met yet.

My other niece and nephew are changing so fast, and I miss my family and friends dearly, but being up here is really special, to feel like every single thing you're doing really matters and to go from having this closeness to the small-team environment, the shared experience, to going back to Earth, much bigger worlds than the space station, and going back to regular life.

♪ It's gonna be complicated coming home.

♪ ♪ Man: Undocking confirmed.

[Indistinct chatter] ♪ Holland, voice-over: It's tough to come back, and the longer the disconnect, you're gonna have more difficulty reintegrating.

♪ How do I prepare people for that?

♪ ♪ When you reconnect, you're assuming that the family is somewhere along the way.

♪ Are they at this place where you left?

♪ Maybe they've changed a great deal, moved on to a new chapter, and they have had their own mission and their own history along the way... ♪ so if you disconnect completely, you're going to be not lost in space, but lost on Earth.

♪ ♪ Male reporter: Cady Coleman, a NASA astronaut, home after her third flight in space, now having logged 179 days in space on her 3 flights, flashing the broad smile that is her signature, also appearing to be in great shape.

Josh?

Josh: Yeah.

Cady is smiling like she always does, and they are beginning to move her over to the chairs.

The crowd here is now clapping for her, and they also have the flowers that they give to her, but she looks extremely, extremely well.

♪ ♪ Coleman, voice-over: It's hard for me to look at you knowing that my kid and my husband might see this... ♪ and to tell stories of thinking about staying longer, that our admission was gonna be delayed and stay longer.

♪ I mean, that was a simple one for me.

♪ If I could have spent another 6 months, I would have stayed in a minute.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ Singers: ♪ Oh, whoa, whoa, oh ♪ ♪ Oh, whoa, whoa ♪ ♪ Oh, whoa, whoa ♪ ♪

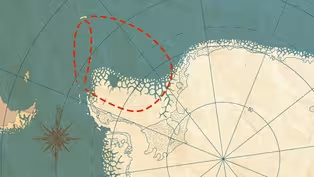

Antarctica's Survival Guide for Mars Explorers

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep16 | 13m 41s | How did the extreme Antarctic winter affected the Belgica's crew? (13m 41s)

Can Humans Get to Mars Without Going Insane?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep16 | 12m 32s | How can future astronauts best prepare themselves to face these challenges? (12m 32s)

Trailer | Space: The Longest Goodbye

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 30s | NASA psychologists prepare astronauts for the extreme isolation of a Mars mission. (30s)

Watch Space: The Longest Goodbye with PBS Passport

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 30s | Get early access with PBS Passport. (30s)

What an Antarctic Disaster Can Teach Us About Getting to Mars

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S25 Ep16 | 15m 9s | How do you keep humans sane and relatively content in isolation? (15m 9s)

Extended Trailer | Space: The Longest Goodbye

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S25 Ep16 | 1m | The grueling journey to Mars. (1m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: