Rhode Island PBS Weekly 6/30/2024

Season 5 Episode 26 | 23m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

The lobster population off the Rhode Island coast is dwindling due to climate change.

Michelle San Miguel reports on how climate change is fueling the dwindling lobster population off the Rhode Island coast. Then, contributor David Wright’s report on why the town of Windham Connecticut has a centuries-long affinity with bullfrogs. Finally on this episode of Weekly Insight, Michelle San Miguel and WPRI 12’s politics editor Ted Nesi discuss the politics of polling.

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Rhode Island PBS

Rhode Island PBS Weekly 6/30/2024

Season 5 Episode 26 | 23m 40sVideo has Closed Captions

Michelle San Miguel reports on how climate change is fueling the dwindling lobster population off the Rhode Island coast. Then, contributor David Wright’s report on why the town of Windham Connecticut has a centuries-long affinity with bullfrogs. Finally on this episode of Weekly Insight, Michelle San Miguel and WPRI 12’s politics editor Ted Nesi discuss the politics of polling.

How to Watch Rhode Island PBS Weekly

Rhode Island PBS Weekly is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(water splashing) - [Pamela] Tonight, losing lobsters in the waters off of Southern New England.

- It's tough work and there's easier ways to make money nowadays.

- [Pamela] Then, one Connecticut town's obsession with frogs, and the politics of Rhode Island polling with Ted Nesi.

(pleasant music) (pleasant music continues) - Welcome to "Rhode Island PBS Weekly."

I'm Michelle San Miguel.

- And I'm Pamela Watts.

Our planet is warming, and it's changing ecosystems all around us.

- Oceans are taking the brunt of it since they absorb heat from excess greenhouse gases.

This has serious implications for marine life in Southern New England, including a summer indulgence.

Tonight we explore why we're losing lobsters off the Rhode Island coast.

This story is part of our Green Seeker series.

- My grandfather was a lobsterman, so he would always go out and he would be on the boat catching the lobsters during the day and then bring it into the restaurant.

Attached to the restaurant was also a fish market, so he'd sell the lobsters at the fish market and they'd cook them up in the kitchen.

- [Michelle] Lobsters are more than a summer staple for 25-year-old Ebben Howarth.

Fishing for them is a core memory from his childhood on Block Island, 12 miles from the Rhode Island mainland.

These days, it's also his way of life.

(traps clacking) Howarth says he had an epiphany several years ago.

If he didn't get into lobstering, it was only a matter of time before there'd be no more commercial lobstermen on the island.

(water splashing) - I felt this pull to just go out and try it, and see if it was something that spoke to me and something that I enjoyed doing.

And when I went out there, I just, it was really, really special.

It was really, really good quality time with my grandfather.

And I just like being on the water.

I like the work itself, it's exciting, it's rewarding.

- Howarth caught no one in his family by surprise when he decided to become a commercial lobsterman seven years ago.

When you first told your family that you wanted to be a lobsterman, did anyone say, "Ebben, you're crazy, don't do it."

- No, it was gradual too, but I didn't ever receive that.

They were always really, really into it.

(motor rumbling) - [Michelle] It's a career fewer people are choosing.

In 2006, there were more than 300 commercial lobster men in Rhode Island, last year, there were 97.

- It's tough work and there's easier ways to make money nowadays.

And I think that if people are given the option, then they'll probably go for an easier, more safe, more consistent way of life.

- But you didn't?

- No, I didn't.

- [Michelle] He knows these traps won't catch anywhere near the amount of lobsters his grandfather harvested on these same waters.

- When he started fishing in, I wanna say it was probably the '50s and early '60s, he said that they would catch anywhere from five to 10 fold what I would catch, and also on a much faster rate too.

(subdued music) - [Michelle] In 2000, lobstermen in Rhode Island brought almost 7 million pounds of lobster to shore.

Last year, they landed just over 1 million pounds.

Scientists say climate change is depleting Rhode Island's lobster population.

Since 1960, Narragansett Bay has warmed three degrees Fahrenheit.

- Lobsters have a fairly narrow preferred temperature range, from about 54 to 64 degrees Fahrenheit.

- [Michelle] Jeremy Collie has been studying lobsters for decades.

He's a professor at the University of Rhode Island's Graduate School of Oceanography.

He says when lobsters are in warmer waters, they exert more energy and metabolism, which leaves them with less energy to grow and reproduce.

- If the water's colder than 50 degrees or warmer than 68 degrees, they'll try to avoid those temperatures, because their survival would be diminished if they stayed in water that was either that cold or that warm.

- How would you describe the lobster population in Southern New England now compared to, say, five, 10 years ago?

- The population is depleted.

- [Michelle] The lobster industry in Rhode Island has had its share of ebbs and flows.

Professor Jeremy Collie oversees a weekly trawl survey at the University of Rhode Island, which goes back decades.

It shows the population of lobsters in Narraganset Bay peaked in the mid '90s.

These days, Collie says, it's at historically low levels.

- I think, ultimately, with climate change, with increased temperatures, this area may become unsuitable habitat for lobsters.

So we really, in that case, lose.

We're kind of at the southern end of the distribution, and so there's always a risk that we're gonna lose that population altogether.

- [Michelle] It typically takes five to seven years before a lobster is big enough to be harvested.

But Collie says many are dying long before.

Young lobsters look like small insects, which make for great prey.

- The predators are mainly other fish species.

- [Michelle] Jon Grant has been a lobsterman on Block Island for more than 40 years.

He says more fishermen are finding baby lobsters in the stomachs of their predators.

- I see it from other guys who catch the scup or the sea bass, and they'll be fileting, "Hey, look there's a baby lobster here."

And then they always like to tell us that.

And now, there's seals.

I mean, we never used to see a seal here past the end of April or early May, and now they're here all year round.

And what are they eating?

- [Michelle] Grant sells lobsters from his boat on the old harbor dock.

He says the atmosphere has changed as fewer lobsters have been found.

- There's no fights on the dock anymore, which, and it's so much less stress.

You know, this, that part of it is great.

- This is where I store the lobsters in between selling them from the docks or if we use them for our catering events.

- [Michelle] Despite that silver lining, those who are catching lobsters in the Ocean State face plenty of challenges, including decades of pulling up lobsters infected with shell disease.

It's an infection on the animal's outer shell.

- And that's actually a bacteria that infects the shell.

And in extreme cases, it can kind of start to kill them, and make them a little bit more lethargic and create infection beneath the shell.

- [Michelle] Research shows warmer water temperatures have been correlated with higher rates of shell disease.

- And the problem with shell disease is that you get a lower price per pound for lobsters.

For example, if I were to sell this one per pound, it would probably fetch maybe $5 or so, where this one could fetch 10 or $11.

- Oh wow, big difference.

- Yeah.

- [Michelle] The disease leaves lobsters with circular lesions, but Howarth says it does not affect the taste of the lobster meat or cause harm to those who eat it.

- What I've incorporated into my business model is buying the shell disease or picking the shell disease that I catch, sourcing it from other local fishermen, and then selling lobster meat prepackaged by the pound.

It's kind of a workaround that I've come up with to be able to still use all the shell disease that I'm pulling in.

- [Michelle] Howarth typically spends two days a week fishing.

When he's not on the boat, he's running his business, Sediment, a sea-to-table catering business with his fiance, Maddy Murphy.

- So we take the lobster that I was catching, we team up with my mother, who is a produce farmer, steal kale from her garden, herbs from her garden, and just bring a simple lobster bake to your table, pack everything in, pack everything out.

Take the hassle out of what eating lobster is for a lot of people, is the mess.

- Where do you see the future of the lobster industry in Rhode Island heading five years from now?

- I see it the way it's been, as just a few guys doing it.

I don't see it really, I don't really think it can get much smaller than what it is and I don't expect it to get any bigger than what it is right now.

- [Michelle] Both Grant and Howarth collect research on lobsters for the Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation, including how many have shell disease and the severity of it.

They receive a stipend for their work.

Howarth says he hopes the information helps shed light on how marine life is changing around Rhode Island, where he says he's living his dream.

- I love that I get to be on the water.

I love that I get to connect with other people and the local food industry, and it's just a really good feeling, seeing that process through.

It's really, really gratifying.

I hope that in five years I'm still doing that.

- Professor Jeremy Collie has also been studying how offshore wind turbines affect the lobster population.

He says, so far, he hasn't seen any impacts.

We now turn to a story about a fight, and not just any fight, but one for the ages.

It started with an obscure bit of colonial history here in New England, dating back to an unseasonably warm June night in the mid 18th century, an episode that went on to be celebrated in story and song, and eventually a piece of modern infrastructure.

And as contributor David Wright first reported in June of 2023, it's a story of one little town's enduring affinity with amphibians.

- [David] Whether you arrive in Windham, Connecticut from the north, south, east, or west, the first thing to greet you is a large green face.

- They've got a lot of character too, don't you think?

- They do.

- They do.

- Four big bull frogs, as solid as anvils, planted there on the Willimantic Bridge, like a concrete lily pad right in the middle of town.

So I'm sure I'm not the first person to ask this, but what's with all the frogs?

(Bev laughing) - So welcome to Windham.

That is a very popular question.

A lot of people who arrive here say, "What's the deal with the frogs?"

- [David] At the pharmacy, and the library on Main Street, the hospital, and the local radio station, Windham honors amphibians.

The town's only real rival in frog mania may be Calaveras County, California, home of the Jumping Frog Jubilee, celebrating Mark Twain's famous 1865 short story.

But Windham's Association with amphibians predates that by more than a century, an obscure bit of colonial history.

- 1754, summertime, it was right in the middle of the French and Indian War, so people were a bit on edge.

And I think, I saw some numbers that there were approximately 100 people living within the general area of this green right here.

- So they heard a noise.

- They heard a noise, and it was about 100 yards into the woods off the road.

- [David] Susan Herrick is an herpetologist, AKA frog biologist, who was born and raised here.

- Men are getting up out of their houses and arming themselves, and yeah, against what they thought was an invasion of either natives or somebody else during this rough period of time.

And everybody was apparently, "afeared for their lives," is what some of the writing is.

- Because of the noise.

- Because of the noise.

- [David] Local historian, Bev York picks up the tail.

- They got their muskets and their pitchforks, and some of the militia started to go up the hill toward the sound.

- What did they think it was?

- Well, they thought it might've been natives.

- They thought they were under attack.

- They thought they were under attack by natives.

- [David] Don't let the peace of the lily pond fool you.

Mating season for bull frogs, happening just this time of year, can get pretty fierce.

(dramatic music) (water splashing) Just ask the BBC's David Attenborough.

- [David Attenborough] The males occupy the center of the pond and fight to hold a place there.

(male frog calling) Their calls will attract females, but they will have to get to the center if they're to meet the strongest males.

- The way that bullfrogs breed is the males who are the biggest and the baddest of the pond set up a territory on the pond edge.

So like if this table were a pond, right, they'd be set up five, six feet away from each other, and they would, you know, sit there all summer, this is my spot.

And they croak with that jug-a-rum call that everybody is so familiar with to tell other frogs that are in the pond, "I'm here and this is my spot and all you."

- Don't even think about it.

- "All you other males buzz off because I'm holding this spot for the ladies."

- [David] Herrick believes the terrible sound that so spooked the locals in 1754 was the result of a colonial climate disaster.

- It's purported that there was a drought here at that time, in 1754, between late June and early July, apparently it was pretty dry.

And I think the pond edge shrunk a little too much, and they gave up trying to hold territories and did what we call mate acquisition strategy switching.

So instead of defending territories, they did what's called a leck, which is where all the males just sort of gather together and display themselves, sort of like a singles bar, if you will.

- So instead of singing a froggy love song, they were kind of having a communal, primal scream.

- Having a mosh pit.

Yeah, exactly.

- [David] In her research at the University of Connecticut, she's spent more than 3,000 hours recording bullfrogs in the wild.

- This is what a frog pond would normally sound like.

(bullfrog calling) - Over here!

- So that's whole songs call.

Now here they start switching notes.

(bullfrogs calling alternately) So they're listening to each other.

- [David] She's built a recreation of what the 1754 frog pond might have sounded like, with all of the bullfrogs bleating at once.

- And this is what I think it could potentially have sounded like on the battlefield, (Susan laughing) so to speak, right?

(many bullfrogs calling simultaneously) - Sounds like a big swarm of angry bees.

Nevertheless, when word got around that this little town had panicked, taking up arms against a bunch of bullfrogs, the story had legs.

- The story had legs, the story had legs.

And from all over, people started talking about the people, those Windhamites who couldn't tell the difference between a bullfrog and an Indian.

- The great Windham frog fight became an American batrachi machia, the stuff of epic comic poems, at least three of them.

Before the US had a national currency.

bank notes issued by the Windham Bank featured a frog standing on top of another frog.

In 1905, the local opera house even mounted an operetta, a musical, "The Frogs of Windham," which has enjoyed several local revivals.

And to this day, the local brewery has an annual hop fest.

So you've embraced the frog, which was originally sort of a joke at Windham's expense.

- A joke at Windham's expense, but we're pretty good at laughing at ourselves, yep.

- [David] The bridge itself is an example of that good humor.

Built 20 years ago by the state of Connecticut, the locals insisted it pay tribute to their heritage.

- Apparently it was pretty embarrassing for the colonists back then.

But nowadays we look back and we laugh, and we think, oh, that that must have been, you know, the equivalent of nowadays online ribbing, you know.

- Yeah.

- Ribbing.

- So forever these frogs will troll the town of Windham.

- Troll the town of Windham forever.

- [David] Willy, Manny, Windy and Swifty may not sing and dance like Michigan J. Frog of Looney Toons fame.

♪ Hello my baby ♪ ♪ Hello my honey ♪ ♪ Hello my ragtime gal ♪ - [David] But Connecticut's famous frogs are hard not to love.

Like the Frog Prince in the 1971 "Tales from Muppet Land."

(tinkly, magical music) (explosion booming) - He turned into a prince.

- How about that?

He really did.

- Murmur of amazement.

(townspeople chattering) - [David] A happy ending in this case for small town New England.

- It brings tourists to town to see the bridge.

That's why you're here.

You came to see the bridge.

- Absolutely.

(light music) - Finally tonight on this episode of "Weekly Insight," Michelle and WPRI 12's politics editor Ted Nesi discuss the politics of polling.

- Ted, welcome back.

Good to see you.

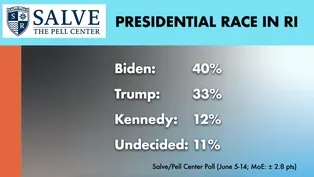

So Salve Regina University's Pell Center recently released this survey of Rhode Islanders who are likely to vote in the upcoming election.

A lot to this survey, but let's start with the presidential race.

The poll shows that if the election were held today, 40% of likely voters would support Joe Biden, 33% would support Donald Trump, 12% would support independent Robert F. Kennedy Jr, and 11% are not sure.

That's a relatively close result, considering that Rhode Island is a reliably blue state.

- That was definitely my reaction, Michelle.

Of course, we always have to give the usual caveats.

This is just one poll, it's just a snapshot in time.

And we should say that there was a University of New Hampshire poll recently of renowned voters that gave Biden a bigger lead than this.

But I do think, when you look closely at the findings, you can kind of understand what's happening here.

It looks like, as we've seen in other polls nationally, Joe Biden has a bit of an enthusiasm problem with Democrats.

They're not coalescing behind him.

Most Democrats are voting for him, obviously, but not to the degree that Republicans are voting for Trump.

And that's why he is underperforming where you'd expect a Democratic candidate to be versus previous elections.

- Let's move on to another result.

The poll shows that 57% of Rhode Island voters agree with the recent decision by a jury in New York to convict Trump in the so-called hush money trial, while 35% disagree, which we should point out that just because people are not supporting President Biden does not mean that they are throwing their support behind the former president either.

- Exactly, I think this result really is helpful for people to think about where the electorate stands in Rhode Island.

You know, there's clearly plenty of Democrats, or Democratic-leaning independents who aren't sold on Joe Biden, or wish they had another option at the moment, but that has not converted them into Trump voters, as we see here.

Here you have almost three in five likely Rhode Island voters agreeing that the Republican nominee is a convicted felon, and should be one.

Not a great base to start from as you're trying to win them over to vote for you.

And then the other thing is the context, right?

Republicans have not won a major race in Rhode Island now in almost 20 years.

Trump's getting that roughly a third of the vote that Republicans consistently get in Rhode Island.

The problem is they can't seem, in any election, to build on that into the 40s, and up to 50% plus one to win.

- Let's look at what the poll found about Governor Dan McKee, who is now in his fourth year in office.

The survey shows only 36% of Rhode Island voters approve of the job McKee is doing as governor, while 54% disapprove, and one in 10 are not sure.

Of course, those are not the numbers that Governor McKee and his advisors want to see at this point.

- No, and it's interesting, Michelle, 'cause when I saw that, part of what I thought about was this is a pattern of governors in Rhode Island having low approval ratings for, frankly, a long time.

Gina Raimondo struggled with low approval ratings, other than during COVID, where she saw a bump.

Lincoln Chafee had pretty dismal approval ratings when he was governor.

Even Don Carcieri in his second term had low approval ratings.

So in that sense, Dan McKee is just, you know, following the trend of Rhode Islanders being kind of down on their governors for quite a while.

But I'd assume that his advisor had hoped he could break that trend rather than continue it.

- Right, but as we know, governor Raimondo was reelected, went on to become Commerce Secretary, so she has done well for herself.

- Yes, you don't necessarily need a wicked high approval rating to win a reelection.

- Well, and back to Governor McKee, you wonder how he would do in the polls had his handling of the west-bound Washington Bridge been different, of course, had that never occurred.

The poll shows that only 29% Rhode Island voters approve of how McKee handled the bridge situation, again, having to close the west-bound side of the bridge, while 59% disapprove.

And this has to be a concern as the governor prepares to run for reelection.

That's not happening until 2026, but of course they're always thinking about that.

- Well, and of course the other problem for him, Michelle, is the bridge is gonna stay in the news because the schedule for demolishing the old west-bound bridge, building the new one, has it that the new bridge is supposed to open right before the Democratic primary for governor in 2026.

So there's gonna be consistent news coverage, developments, you know, how this project is handled.

Is there more disruption for drivers?

Is it on time?

Is it on budget?

All of that, I think, is gonna be in voters' minds, maybe not every day, but it's gonna keep coming up over the next two years and be one of the ways they're judging the governor.

In the short term, the big question right now is what will the cost actually be to take, to build the new bridge?

We're waiting for those bids in July.

I think that's gonna be a telling moment coming right up.

- And it's worth stressing too with these polls, it's one brief snapshot of a moment in time.

We both know that things can quickly change.

If this poll were conducted, say two months from now.

- Absolutely, you remember, you mentioned Gina Raimondo.

Think about what happened there.

She had been fairly unpopular.

Yes, she won reelection, but her approval rating had never been great during her time in office.

COVID hits, people liked how she handled that initially.

She saw this wild surge in her approval rating.

So yeah, people, crises, I think it shows here, crises can change people's opinions one way or the other.

I think for McKee, the bridge crisis hasn't been a time voters were thrilled, clearly, with what he was doing, and that's been a problem for him.

But maybe he can turn that around, or maybe a different crisis gives him a different opportunity.

- Thanks so much, Ted.

- Good to be here.

- And that's our broadcast this evening.

Thank you for joining us.

I'm Pamela Watts.

- And I'm Michelle San Miguel.

We'll be back next week with another edition of "Rhode Island PBS Weekly."

Until then, please follow us on Facebook and X, and visit us online to see all of our stories and past episodes at ripbs.org/weekly, or listen to our podcast on your favorite streaming platform, goodnight.

(pleasant music) (pleasant music continues) (pleasant music continues) (pleasant music continues) (pleasant music continues)

Video has Closed Captions

The lobster population off the Rhode Island coast is dwindling due to climate change. (9m 13s)

Video has Closed Captions

Why a small town celebrates its heritage by honoring frogs. (8m 31s)

Video has Closed Captions

A poll finds the race for president is close among Rhode Island voters. (5m 10s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipRhode Island PBS Weekly is a local public television program presented by Rhode Island PBS